|

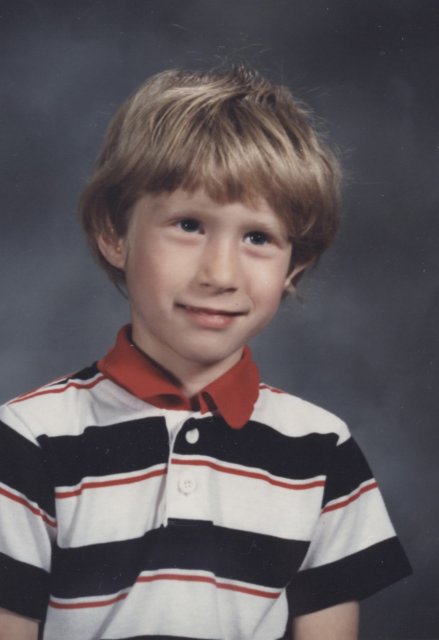

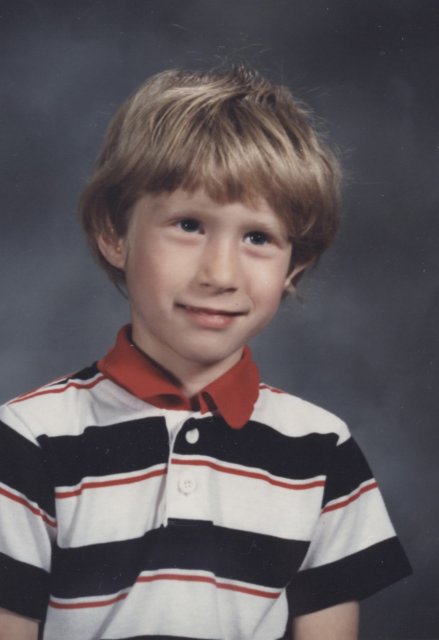

A wonderful boy who

became a fine young man, Brandon Hampson was born on August 11,

1985, and welcomed warmly into his family by his parents and two

older sisters. He was a happy baby and a playful toddler,

though his birth weight had been just over five pounds and his

growth and development seemed somewhat slow. When he

hadn’t learned to speak by the age of three, his family grew

worried and took him to Providence Speech and Hearing for

testing. There he was diagnosed with mild to moderate

sensorineural hearing loss in both ears, probably, it was said,

due to heredity. An MRI run shortly after this showed no

brain abnormalities.

Brandon was fitted with

hearing aids, which he wore forever after without ever a single

complaint. He started preschool in a communicatively

disabled program, and for three years had one of the most

wonderful educational experiences of his life. By the time

it was over, he was ready to begin “real” school, and came home

to his neighborhood elementary. Learning here was a

struggle at first due to his late start with language, but he

still experienced great gains, starting out as a non-reader and

making 2 ˝ years progress in the first year alone. It was

always necessary for him to work hard at expressive language,

but by the time he was in fifth grade, he nearly always managed

to make honor roll, and thought of himself as one of the “smart

kids.”

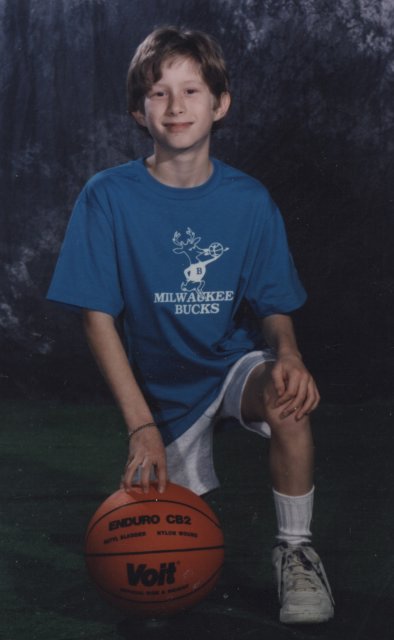

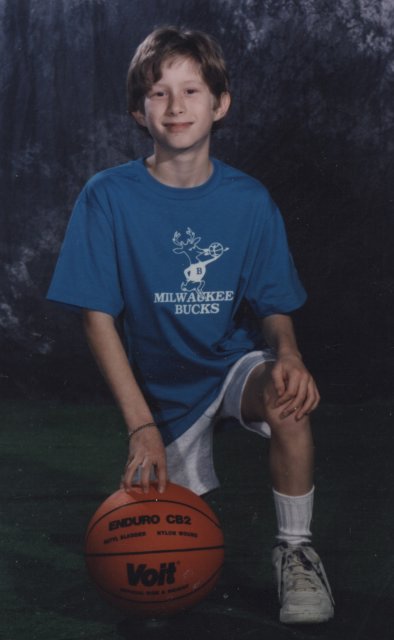

During his elementary

years, Brandon made friends, enjoyed Boy Scouts, played Little

League and NJB Basketball and pursued hobbies including inline

skating, building with Lego blocks and playing video games.

Although he never liked music as a child, he joined the

elementary band playing trumpet, and from then on, music became

one of his passions. He always was close to his sisters,

and the family made a point of having dinner together and taking

long vacations to far-away places, eventually visiting 36

states, eastern and western Canada and Europe.

In junior high, Brandon

was shy but well liked, and his family always was amazed by how

many kids knew him and stopped to say “hi” when they went out.

He was one of nine seventh graders named as school-wide students

of the month, and the very first eighth grader (from a class of

500) selected as Rotary Junior Citizen of the Month. He’d

had to struggle as a kid, had a strong sense of the importance

of helping others and invariably was kind to all. He

joined the junior high band (now playing drums), was selected

for National Junior Honor Society and volunteered with the

school tutoring program every day during lunch. He was a

good student, and at graduation received several honors and

savings bonds. In his spare time, he continued in Scouts,

doted on computers, loved composing music and began studying

karate at a wonderful studio.

Brandon’s freshman year

in high school was a difficult one, as many changes challenged

his household. He always had remained close to his

sisters, but for the first time they both were away at college.

Mom, who all his life had been there when he got home from

school, returned to teaching full time to help support their

tuition. He registered for a full schedule of classes and

chose to enroll in marching band and cross-country running, two

extremely time-consuming activities. Many of his junior

high friends had not gone on to Brea Olinda High School, and the

network of friends he had left broke apart that fall.

About the same time, his only grandpa got sick, was diagnosed

with cancer, came to live in our home and died almost as soon as

he arrived. Brandon struggled with sadness and was often

ill, yet persevered. Despite encouragement to lighten his

schedule, he didn’t think it was right to quit something once

he’d begun, and stuck with both band and cross country through

the end of their seasons.

By sophomore year, some

changes were made. Mom gave up her job and Brandon

lessened his activity load. From here on he would focus on

things he loved and work to find ways---even if he had to invent

them---to be able to do them. As a member of the

hearing-impaired community who’d grown up without learning ASL,

he pushed to be allowed to study sign language in high school,

so that he could better relate to others like him. He had

a tutor freshman year, but loved studying the subject so much

that he convinced school administrators to offer an after-school

ASL class the following year. Nearly 30 students signed on

for the new credit course. He volunteered to serve as a

student member of the WASC (Western Association of Schools and

Colleges) accreditation study team, and loved the many months of

interaction he had with students, staff members and parents

assessing his school’s strengths and weaknesses.

He discovered the school

had no viable internet presence, and proposed that that should

change, finally persuading the vice principal to let him have a

crack at it. By junior year, the school’s website had been

transformed into a widely used communication tool, with Brandon

as its webmaster. His shared his technology expertise on a

regular basis at school, helping staff members set up hardware,

install software and troubleshoot systems, preparing all

the charts and graphs for the final WASC report, and assisting

the counseling department in creating three separate state and

national service “report cards,” all of which won major awards.

He provided technical assistance to the school district,

scanning historical photos onto discs and assisting with the

district’s 100-year anniversary celebration book. He

designed the T-shirts all senior students wore to their grad

night. He did all the technology support for two of his

mother’s school board campaigns, including maintaining websites

and formatting all her published materials.

Outside of technology,

his major love in high school was instrumental music. A

four-year member of the BOHS Marching Band (carrying the biggest

bass drum) and percussion ensemble, he also enrolled some years

in concert band and wind ensemble. He was a band officer,

cataloged the band music, worked every fund raiser, came early

and stayed late to help load and pack up for every football

game, field show, parade, concert and competition, and just

generally gave his heart to the group in all its efforts.

It was here that his friends were and here that he learned what

it was like to be part of a group that worked hard and met with

success. His last act of volunteerism, right before he was

diagnosed, was serving as a percussion instructor at summer band

camp.

During his free hours,

he socialized some with friends, going to band parties or

organizing Friday afternoon runs to Baja Fresh. He learned

to drive late, but got a new car during senior year, and loved

to take the underclassmen home from school. He didn’t go

out all that much, but had friends over to play computer games,

read a lot, kept up with politics and current events, went to

karate and worked for hours on computer projects. When his

sisters were home, he spent a great deal of time with them.

When they weren’t, he was the kid most likely to be seen with

Mom and Dad, at Fry’s or Best Buy, eating pizza, going to the

movies, helping around the house or just “hanging out.” He

formed strong adult friendships with his long-time

hearing-impaired teacher, the high school assistant principal

with whom he worked on the website, the band and percussion

directors and the paid tech staff at school, and enjoyed

socializing with them as well.

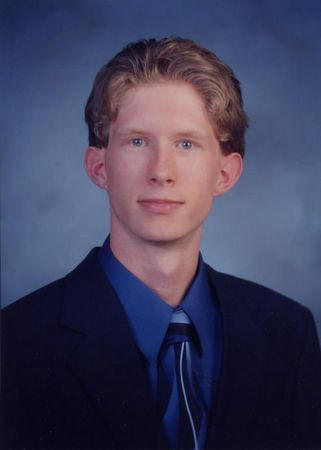

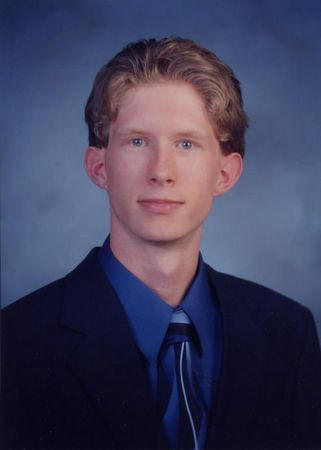

Overcoming the odds (an

astonishingly few hearing-impaired students do well in high

school and go on to college), Brandon became a good student.

He took honors and AP classes, generally earned A’s and B’s and

graduated with a 3.6 GPA He didn’t drive himself as hard

as his sisters had, but enjoyed his time, and balanced homework

with the real contributions he was making to school and

community. He seemed extremely well adjusted for a young

man of his age, and impressed kids and adults alike with his

friendly demeanor and humble yet self-assured ways. He

was one of the first four students in his class inducted into

National Honor Society, and was honored at graduation with the

Mayor’s Youth Community Service Award (for 500 hours of

volunteerism), the Marine Corps Semper Fi award (for musical

excellence) and a special first-time technology award created

just for him by the school’s administration. In honor of

his contributions, the PTSA also later recognized him with its

honorary service "very special person" award. He was

accepted at every college he applied to, but settled on Chico

State. The town and campus reminded him of Davis (where

his oldest sister had gone) and the school offered a rare

business administration-computer systems management major that

seemed tailor made for him.

He spent the summer

following graduation engaged in volunteer work and polishing up

his academic skills, getting some tutoring in math and working

with Mom on English. He helped out enormously when the

local historical society dedicated its new museum, gave two full

weeks to band camp, and had the time of his life at SuperCamp!

College Forum in Colorado Springs, the first time he’d been out

of state alone. He turned 19 in August, and was poised to

begin a new chapter in his life when everything suddenly changed

in the space of an afternoon.

He’d had an eye exam in

early August, but when his contact lenses arrived, something

didn’t seem quite right. He assumed the prescription was

off a bit, but was temporarily preoccupied and put getting it

fixed on the back burner. When band camp was over, he

drove himself to the optometrist, and learned that the problem

was more complex. His suddenly “uncorrectable” vision led

him to a neurologist, into a series of ever-larger MRI machines

and finally to the offices of two neurosurgeons, who determined

that only a look inside his skull would do. Dr. Keith

Black of Cedars-Sinai, reputedly one of the world’s finest brain

surgeons, performed a biopsy by full craniotomy on September 10,

and learned the golf-ball-sized tumor behind his left eye was

Anaplastic Astrocytoma.

Having cancer at 19

would have been bad enough, but two days later he began to

hemorrhage. He coded out in the CAT scan, and emergency

surgery was needed to relieve the swelling in his brain.

The left front portion of his skull had to be removed, but

he survived, even though the hemorrhage extended from the

temporal lobe all the way to the basal ganglia. He was in

ICU for more than two weeks, then a regular room and then rehab,

altogether spending nearly two months in the hospital. He

woke up 20 pounds thinner, with significant vision and

short-term memory loss, as well as major weakness on his right

side. He was unable to walk, swallow well or use his

dominant hand. He had to have a tracheostomy and then a

feeding tube, then radiation and chemotherapy. Slowly and

with great effort (as well as the help of some wonderful

therapists), he began working to get his life back. He lifted

more and walked farther than anyone ever asked, and slowly

earned his freedom from a wheelchair. He did speech

exercises again and again to strengthen his “paralyzed” throat,

and got his swallow back in two months instead of the six months

to a year the specialist predicted. No matter how tired he

was, he never complained, always worked hard and invariably was

pleasant to all who helped him. Not surprisingly, he

became a favorite wherever he went. He continued on

chemotherapy, and MRIs showed his tumor to be steadily

shrinking, progress his doctors called “amazing” and even

“miraculous.” By March it no longer could be seen.

At home he continued to

progress, walking more than a mile a day, eating well, taking up

meditation with guided imagery, and doing all that he could to

get well. He was strong enough by February to have the

missing “bone flap” restored with a prosthetic piece, and seemed

to recuperate better than expected. He had five wonderful

weeks, but then Staph infection set in, and another surgery was

needed to take the prosthesis out. He was on IV

antibiotics for a month, but didn’t seem to get well, and began

to experience pain in his back and legs. Soon he was back

in the hospital, this time to have a shunt installed to relieve

fluid build up in his brain. The MRI taken just prior to

this surgery revealed some startling news, as the cancer which

had seemed to be well in retreat now appeared active throughout

his nervous system. There were several new spots in his

brain and, for the first time, lesions also appeared on his

spine. The entire lining of his brain and spinal column

glowed, seemingly coated with a covering of cancerous cells.

He was in the hospital

for another two weeks, and came home significantly weaker and

thinner than ever before. He began a new round of therapy,

with whole-brain radiation and radiation to almost his entire

spine, along with chemotherapy. Every doctor and therapist

he saw seemed to think he’d be devastatingly ill from side

effects, but all he experienced was fatigue and a little dry

throat. He never even lost his hair. He was very

tired, but he still worked as much as he could to do well,

eating everything placed before him and exercising all that he

could. He continued to be the same sweet, positive,

uncomplaining young man he always had been, one who was deeply

loved by his family, his friends and many, many people in his

community, as well as the wider world.

From the time he was

first diagnosed, so many people were interested in his welfare

that Mom and Dad had to start e-mail updates because they just

couldn’t keep up with the phone calls. Throughout the

months, these communications continued, and Brandon’s upbeat

attitude and fighting spirit inspired scores of people, many of

whom forwarded them on to others around the globe. The

friends he had, and the friends he made after his illness became

known, showered him with cards and calls, visits and good

wishes, and their prayers were felt both by him and his family.

Although his energy and

his ability to concentrate sometimes were sadly limited, during

the final days of his life, Brandon enjoyed visits with many old

friends. In early June, he was thrilled to have the Brea

Olinda High Marching Band play a short concert in his honor

right in front of his house. In a ceremony held at his

bedside June 22, he was deeply touched to be awarded his First

Degree Black Belt in karate. Bestowed by the leaders of

Fullerton’s American Martial Arts Academy, it recognizes both

rank advancements made before he became ill and the great grace

and strength of character he showed in the months following his

diagnosis.

Brandon passed from this

world on the afternoon of June 26, 2005. Even in death, he

continued his lifelong mission of “helping people,” by donating

his corneas---all that he had left to offer---so that someone

he’d never met might regain the precious gift of sight.

|